Is there proof of an afterlife? So asks the title of a Deepak Chopra essay that I read on Medium.com.

I can’t remember why I read it, as I’m not a fan of Mr. Chopra’s wisdom.

But I did. I read that essay so that you don’t have to. I took one for the team.

You’re welcome.

In the setup of knower-known, and process of knowing, all three elements are unified — you cannot have one without the others. Therefore, separating out the physical body and giving it a privileged position is invalid. There is nothing about the drying body that proves the extinction of life, any more than the dying away of thoughts proves that the mind is dying. Every phenomenon is transient, yet life persists even as cells die every day…

Deepak Chopra, ‘Is There Proof of an Afterlife?’ Medium.com, 23 July 2019

By the end of the essay, Mr. Chopra doesn’t come any closer to answering his question than he did when he wrote the title.

Put it this way: if what he wrote answers anything, it is not the titular question.

But I want to run with something incredibly life-affirming that Mr. Chopra said in that paragraph above. Possibly the only factual statement in the entire piece.

“There is nothing about the drying body that proves the extinction of life…”

I agree wholeheartedly with that statement. Far from the extinction of life, the drying body veritably shouts out life and living.

Bath time

Each of us has subconscious memories of being bathed by our carers – and probably even subconscious-er memories of floating in amniotic bliss – and then being lifted out of the water to be cocooned in the warmth of an embrace wrapped around a towel.

Most parents will remember the first time we bathed our first baby, in a tub on the kitchen table, water temperature just right – dip your elbow in to check – and the meticulous care we took to make that first experience wonderful. And we all probably mistook our baby’s recognition of the sensation for a look of surprise at a new experience.

Baby’s “first” bath is one of the first of many milestone celebrations of life.

Beach time

What about the first swim of the summer, when the water in the pool or at the beach hasn’t yet warmed up – here in New Zealand, some would say that the water at the beach never does – and there is that full-body relief when you get out of the water and wrap yourself in a towel?

At that moment, you know for sure that you’re alive, courtesy of your drying body. I have a vivid memory of blue lips, chattering teeth, goosebumps. The joys of a skinny-bodied boy in the early summer of a temperate climate.

And then there’s the universal activity of jumping into water. Off a cliff, off a boat, off a dock, into a swimming pool. And the well-earned drying-off in the sun afterwards. There are not many better summer pastimes.

Jump, get out, climb back up, jump, get out, climb back up.

Then lie in the sun to dry out and warm up.

Repeat.

When you’re lying in the hot sun, the top of your body heated by the rays of the sun, the underside soaking up the warmth radiating from the hot concrete or sand beneath you, and you find yourself still shivering, your teeth chattering, you know beyond a shadow of a doubt that you are alive.

Bathhouse time

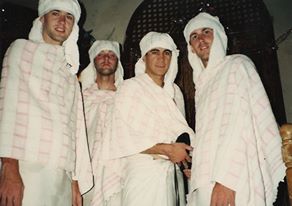

Finally, I have fond* memories of being subjected to a gruelling ordeal in Hammam Yalbugha, a public bathhouse in Aleppo, Syria, in the early 90s. (As a result of the recent civil war, the place, built in 1491, now looks like an archaeological ruin.)

I recall ill-fitting (single-use, please, please, they were single-use) shorts, copious quantities of hot, flowing water, and then ten minutes of Graston technique (“an instrument-assisted soft tissue manual therapy“) with a coarse sponge and even coarser soap.

Aleppo soap is famous, made from olive oil and laurel oil. They must not have bothered to remove the stones when making the soap that was used on me.

And the sponge. The sponge was a weapon on the hand of an old Syrian man with a sadistic grin on his face and whistling through his tooth.

There was a language barrier. In retrospect, I think he may actually have been the janitor, but when he said something in Arabic to us – probably telling us the floor was wet because it had just been mopped – one of our party went over to him and lay down on the slab, so he went to work on us, one by one.

A language barrier, yes, but the language of pain breaks down that barrier.

The old man must have seen it being done before, because it felt to us as if he knew what he was doing – if our expectation included gruff, rough, unforgiving scrubbing of the outer dermal layer to within an inch of its life, on every square inch of our bodies.

He must have had a chiropractor or contortionist in the family, too, such were some of the things he made my body do. Surprisingly, there was no blood in the water. (That day, or the next.)

The experience of sitting and sipping from a glass of hot and incredibly sweet Syrian tea in the recovery room, complete with warm dry towels wrapped around head, shoulders and waist, was divine.

Sitting there, sipping tea, as our skin gasped for breath and our bodies dried. Now, that was living!

Thank you, Mr. Chopra, for the memories you’ve evoked.

* I’m not sure if I’ve found the right word to describe that experience.

(Top image by MitaStockImages, depositphotos)

Be First to Comment