Where do you think this quotation has been lifted from?

If I were asked that, I would venture that perhaps it was an art commentary or an opinion piece in an upmarket magazine or newspaper.

What about a 288-page decision by a Federal District Court judge in Tallahassee, Florida, USA?

That’s right. Judge Mark E. Walker uses this analogy on page 39 of his 31 March 2022 decision “on the legality of Florida Senate Bill 90—a sweeping package of amendments to the Florida Election Code—that Plaintiffs challenge under the First, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the Voting Rights Act (VRA).”1

A 288-page legal decision!

Why?

Who?

Who, but an election lawyer, law student, or journalist would plough through such a boring document as that, filled with turgid2 legalese and obscure precedents, as well as simultaneous references to highbrow art history and decidedly lower-brow Ferris Bueller’s Day Off?

Wait. What? Ferris Bueller’s Day Off?

I kid you not.

Footnote 13: See Emma Taggert, How the Pioneers of Pointillism Continue to Influence Artists Today, My Modern Met (Jan. 18, 2018), https://tinyurl.com/ybux3r5s; see also Ferris Bueller’s Day Off – Art Institute of Chicago scene, YouTube (Nov. 21, 2011) https://tinyurl.com/2ce925m91 (p. 39)

As is customary for me, I followed the links to learn about the pointillism movement and what artists like Georges Seurat were aiming to do with their new neo-Impressionist technique. (Did you know that, like the term “Impressionism”, “pointillism” was coined by critics of the movement? No need to name your own style – let the scoffers do it for you.)

The Ferris Bueller link took me to a YouTube video showing Ferris, Sloane and Cameron during their visit to the Art Institute of Chicago. The main actors in this segment are the paintings and sculptures upon which the camera lingers, almost lovingly: Kandinsky, Matisse, a collection of Picassos. And…

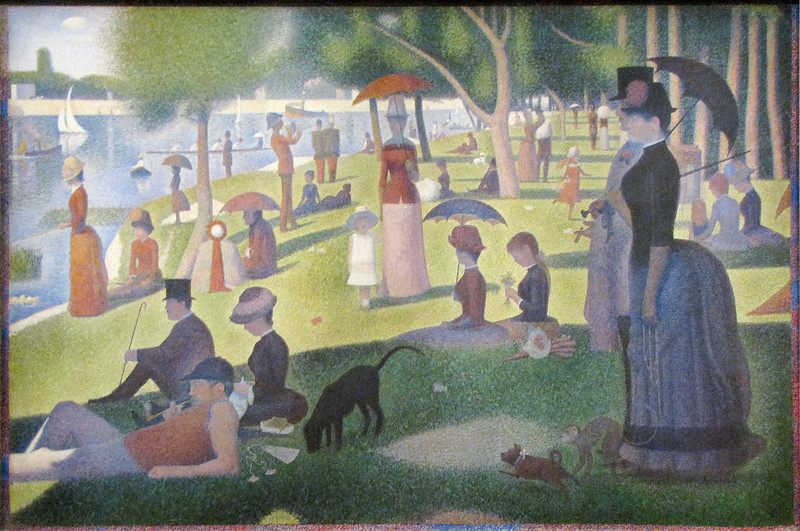

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

And this piece.

Seurat’s work is the undeniable star. The viewer watches Cameron as he views the larger-than-life painting and is visibly moved by it.

As a perfect illustration of Judge Walker’s analogy, the camera starts with a shot that contains the entire impressive two-metre-high, three-metre-wide painting and Cameron standing in front of it in contemplation.

(La Grande Jatte is an island on the Seine in Paris, and in the late 19th century when Seurat painted the scene, it was a place where Parisians went to relax. Three dogs, eight boats, forty-eight people and a capuchin monkey3 were there on the day that Seurat decided to immortalise on canvas. Although, he did take two years to paint the scene, making sixty sketches before putting oil to canvas, so the chances are that the inhabitants of the painting may be an amalgam of the many who enjoyed the park on the days that Seurat worked on site.)

Next, the camera has come forward and is looking over Cameron’s shoulder. The painting takes over the entire background of the shot. Then, the camera moves to a position between Cameron and the painting, alternately capturing the changing expression on his face and zooming in closer and closer on the face of the little girl standing next to her mother near the centre of the painting.

As the camera zooms closer, the features of the girl’s face begin to lose their definition, until an extreme close-up shows no discernible representation of anything at all – just an array of white dots of paint.

When the camera switches to Cameron, it focuses on his furrowing brow as his expression changes from one of contemplation and appreciation to one of increasing concern.

Or perhaps it’s realisation. Dread, even.

What is it about this painting that moves him? Clearly, it is something to do with the loss of detail that occurs with closer scrutiny.

But, just as clearly, it’s not the painting he’s worried about.

Why?

Is it important that we know why it moved him?

Judge Mark E. Walker of the Federal District Court, Tallahassee, Florida, provides not the answer, but a clue.

As it turns out, he comes at the answer from the opposite direction.

The context of what he is talking about is unimportant to this present post – in case you’re curious, he is discussing the matter of motivation for passing a law, and the necessity for inferring the intent of the Legislature from the available circumstantial evidence when that motivation is not specifically stated – but what he gives is a principle that can be widely applied:

Think of it like viewing a pointillist painting, such as Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. One dot of paint on the canvas is meaningless, but when thousands of dots are viewed together, they create something recognizable.13 So too here, one piece of evidence says little, but when all of the evidence is viewed together, a coherent picture emerges.1 (p. 39)

Like the small individual textured dots of white that make up the face of the little girl in the middle of A Sunday Afternoon, single pieces of evidence don’t tell the whole story and may appear to have little value on their own. They’re essentially meaningless at that level. But, when viewed from big-picture range – standing back and looking at the entire work – the thousands of individually insignificant pieces together create a picture of unarguable significance.

There is a valuable lesson in that for everyone – not just Federal Court judges and the people who read their 288-page decisions.

One example. Every hour, every day, for hundreds of days of monotonous training in a gymnasium, in a swimming pool, or on the athletics track – each individual snapshot of time may seem to have no meaning of its own to the casual observer of an Olympic athlete in training. No single lap of the pool or the track will be the winning of a medal, but the athlete knows, like Seurat, what the final picture might look like and is willing to put in the time and effort to complete it.

Art history. Olympic history. Parenthood.

The mundanities of life well lived that lead, in the end, to the work of art that was a life well lived.

The principle is eminently applicable.

Cameron

But that’s not what moved Cameron.

The movie does not tell us what affected him so much. To me – not the most perceptive of movie-watchers – it seems to treat the segment as a whimsical interlude. Then it moves on.

As would have I, too, had I not seen the next video YouTube’s algorithm had in store for me: ‘John Hughes commentary: the Museum scene from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.’

The video is a repeat of the scene, with the director providing an explanation of why the movie even went to the Art Institute in the first place.

Hughes admits it was self-indulgent. The Institute had been a refuge for him during his high school years, a place he had come to enjoy and appreciate. The paintings filmed were his favourites, the ones that had moved him so much in his younger years that he wanted to share them with his audience.

Cameron’s interaction with A Sunday Afternoon related to the non-existent relationship he had with his father.

Just as it had for Hughes in his teenage years, the Art Institute provided Cameron a refuge, if only fleeting, on this particular day that also was a temporary refuge of sorts from his regular life.

In his commentary, Hughes says that it is while studying the girl standing beside her mother in Seurat’s painting – and seeing how the closer he looked at her face, the less he saw – that Cameron is confronted with the worrying possibility that he, too, may not bear up to scrutiny. He fears that the closer you looked at him, the less you would see.

That ‘there isn’t anything there.’

Hughes stops there in his commentary, but we need not do the same.

Stand back

Rather than zooming in on ourselves, or others, until all we can see is every mistake, every shortcoming, every sin, a better approach may be to stand back.

It feels like each of us is more than the sum of our parts.

Rather than scrutinising every pore, or every cell, or until all we’re left with is a (very large) handful of atoms, perhaps we should take Judge Walker’s advice and ‘think of it like looking at a pointillist painting’.

- https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/21564733/ndfl-voting.pdf (p. 2)

- ’Turgid’ is defined in Merriam–Webster as ‘excessively embellished in style or language’. Possibly not the exact meaning I was after, but it sounds like the word I want to use.

- https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/sunday-la-grande-jatte-georges-seurat/

[Top image: “‘A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884’ by Georges Seurat” by mark6mauno is marked with CC BY 2.0.]

Comments are closed.